by Lynn Colburn Shapiro

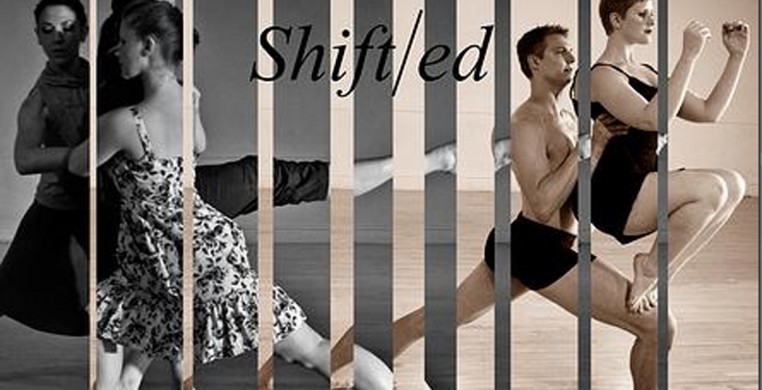

Names and titles can inform or confound, inspire curiosity or obscure meaning. Esoteric Dance Project’s co-artistic director/choreographers Christopher Tucker and Brenna Pierson-Tucker have done all of the above in “Shift/ed,” a program of four new works presented at Links Hall over the weekend.

On the plus side, each of the pieces was eminently watchable, cleanly executed, and clear in design, choreographic invention, movement vocabulary, and theme. There was nothing “confidential, intended or understood by a select few, exclusively for the initiated, or abstruse” about them (Webster’s definitions for “esoteric”). So far, so good! On the other hand, all four works were well within the boundaries of safe, secure conventional forms, with a couple of forays into areas that promise to burst into bloom with a voice all their own.

Program opener, “Em-Em-Dubs,” (the title’s reference eludes me) offered up five sunny women in a theme-and-variations structure that explored a fluttering hand gesture set to a percussion-rich score by Medeski, Martin and Wood. Beginning with linear gestures and stop-action poses, the piece built nicely to more flowing arcs, athletic lifts, barefoot bourees, and liberal use of the space in running and jumping sequences. Pleasant enough, the movement drew from recognizable concert dance idioms and kept a brisk pace to the snappy percussion beat. Movement vocabulary showcased the ensemble, minimizing the dancers’ distinctively different body types, sizes, and levels of technical proficiency with material accessible to each of them. Their primary-colored tunics painted the stage with a playful moving palette, and the dancing held attention, albeit without marked choreographic innovation.

In “After The Nickel Runs Out,” the evening’s most interesting work, title and choreography informed each other as three of the group’s strongest dancers portrayed working girls from the early days of cinema. Dressed in period dance hall costumes, the women could have been refugees from a debauched circus. Their drama unfolded in episodes alternating their on-camera, unison “fakeyness,” with their off-camera emotional reality. The dancers’ larger-than-life shadows across a flickering light projection on the back wall created the image of an old-time movie in which the women were at once trapped in an unchanging past and endlessly repeating an unbearably painful present beneath pasted-on smiles. A grainy recording of Eddie Cantor singing “The Dumber They Come The Better I Like ‘Em,” (“‘cuz the dumb ones know how to make love...”) added both context and ironic commentary. Once “the nickel ran out,” Cantor’s voice and the projection shut off, and movement shifted abruptly into an inventive tapestry of longing, escape, and internal struggle characterized by dive rolls, passionate abandon, desperate running, smashing against the back wall, and driven turns and extensions. Dario Marianelli’s lush, flowing orchestral music made fitting accompaniment for development of individual characters. The sound of a coin dropping into a box and the rusty gears of an ancient projector grinding slowly into motion signaled their return to the movie motif, Cantor’s song, and their life-sentence to unison repetition of silver screen cliches. The choreography gave dancers Allie Buchweitz, Dylan Roth, and Sarah Schmitt ample opportunity to use their considerable talents, but alternating sequences became predictable in both length and dynamic, never quite building on the promise that something else might happen and lead to a fully-realized ending. What else could these women have dreamed and lost? What keeps them always returning to the trap of their on-screen personas? The piece is too good to let go yet, and one would hope its enterprising choreographic team will continue to explore possibilities.

The second half of the program offered “Translate to 2,” a brief duet for Pierson-Tucker and Schmitt, and the more fully-developed “Chiaroscuro,” which again integrated projection into the choreographic fiber of the piece. The abstract design of black and white swirls and peaks that was projected onto the back wall also patterned onto the dancers’ skin and costumes as they moved in and out of its path. Static visual art became a living, breathing organism swirling over the dancers’ bodies with a movement all its own. This truly-blended use of visual art and dance was exciting and is worth exploring in future work. “Chiaroscuro” brought the entire eight-member ensemble onstage in movement patterns that mirrored the swirls and dips of the visual art. Costumes extended the theme, with five dancers in light tops and dark, floor-length skirts, and three dancers, including the company’s sole male, Christopher Tucker, in dark tops and light skirts. Seeing a male body among the flock of female dancers for the first time all evening had a galvanizing effect, not only because of Tucker’s strength as a dancer, but because of his size (very tall and muscular), and the variety of texture the introduction of a male body in motion and in stillness immediately adds to the stage energy. One has to question the choice of costuming in light of this fact. Dressing the women and Tucker all in skirts made a very loud statement: see, we are all the same. And yet they were so clearly gender distinct that the costuming, rather than relieving the audience of gender awareness, accentuated it and drew attention away from the more pertinent aspects of the piece, which was ostensibly about the interplay of light and dark.